As a seasoned computer science teacher and curriculum manager, I believe that all strong computer science curricula have appropriate scaffolding, are project-based, and are easily and effectively differentiable. I’ll be writing a series of posts on each of these attributes, but today, I’m going to do a deep dive into scaffolding.

I’ve written a lot of CS curriculum. Hundreds of hours worth (perhaps thousands), for my classroom, for my own company and for other companies that valued my expertise. As a high school teacher, I’ve also used countless other curricula, some very effective, and many fair to terrible. Because I’ve had first-hand experience with so many curriculum products, I know that a poorly scaffolded curriculum is detrimental to student outcomes.

Without the right scaffolds in place, students won’t develop independent thinking, and may give up entirely before they’ve started.

What is scaffolding?

If you’re not an educator, this word probably makes you think of the temporary support structures used by construction workers to reach tall places. On the other hand, if you’re a teacher, your primary association may be something else.

In the education world, “scaffolding” has a specific technical meaning. It refers to the way that a teacher or curriculum slowly removes instructional supports as students learn. The goal of scaffolding is to guide students to independent thinking and problem solving. We want students to learn how to approach a wide range of problems, not just the specific task at hand.

Scaffolding is important for learners in every field, but it’s particularly relevant when teaching computer science.

Most K-12 learners have little experience writing code, so they’ll need extra support up front. Writing code is a skill. Computer science learners are not just memorizing facts or syntax. They’re learning a new way to think. If we want them to master skills, we must guide them towards independent thinking.

Scaffolding for CS

So what does scaffolding look like in a computer science curriculum?

At the start of a project, you’ll want to be very explicit in telling students what code to write and where. If a student has never written an if statement or a for loop, you can’t expect them to understand how to do it just by hearing the theory behind it and seeing a syntax example.

As a project goes on, students should receive less support. Each step should require a little bit more independent thought. Students build on what they’ve learned, slowly learning not just a programming language, but how to use code to solve a problem.

Ideally, we’re teaching them not just the “what” of programming, but also “why” and “how.”

How do you know if a curriculum isn’t scaffolded enough?

Unscaffolded computer science curriculum falls into one of two extremes.

The first extreme gives too little support to students. It provides abstract information and then asks students to perform a concrete task.

An example assignment might show students the documentation for the Java class String, and then ask them, “find and use methods in this documentation to write a new method that states whether a given input String is a palindrome.”

This assignment leapfrogs several levels of thinking, asking students to synthesize lecture material without ever getting them to analyze or apply. It doesn’t even check for comprehension.

The second extreme gives too much support. It will give students project to work on, but will spell out what to do for every step along the way, like a recipe. An example assignment that gives too much support might be a video tutorial called “How to Build Space Invaders in Python with PyGame,” that never pulls back and asks a student to figure out the next step themselves.

Students will end the assignment with a finished product, but they won’t ever be required to solve a problem. They’ll be told exactly what code to write the whole time.

Both extremes cater to the students who don’t need a teacher.

An exceptionally self-directed student given too little support will find a way to solve the problem. This will probably involve doing research and practice outside of the curriculum to gain the support lacking in the assignment.

An exceptionally self-directed student given too much support will think outside the task at hand to learn why the project steps work. This will probably involve experimenting and adding new features not requested by the assignment.

Meanwhile, the students who need a teacher never really learn anything.

If you don’t give your students enough support, they’ll have nothing to show for their frustration, and probably won’t want to keep learning to write code.

If you give your students too much support, they’ll never learn to write code beyond following a set of steps. Students will never get to be creative, and they won’t feel like they know what they’re doing.

How to do it right

What does a properly scaffolded computer science curriculum look like?

As I said in the introduction, I’ve written countless computer science curricula. Many different courses, for a variety of companies. Sometimes I had the freedom to craft a curriculum’s direction myself, other times I had to follow the style and goals of a different curriculum manager.

Whenever I was designing the whole curriculum myself, I used the following structure for every lesson:

-

First, students read about a new code concept or structure. They’ll learn a big idea and some syntax. The concept might be something like arrays, class inheritance, or Boolean operators.

-

Next, students watch a short video showing someone write code using the new concept. They get to see the skill applied, along with an explanation for how and why it was written that way.

-

After the short text and video lessons, students start working on a project that uses the concept.

All of the real student learning happened in part three. Delivering new content with text or a video is necessary, just like lectures are necessary, but all good teachers know that watching videos or listening to a lecture is one of the worst ways to learn. Students don’t internalize knowledge or develop new skill until and unless they’ve done hands-on work. Similarly, all good curriculum writers know that hands-on work is where you have to scaffold.

If we don’t have enough scaffolding, students stare at a blank screen forever (or immediately use their favorite AI tools to get the correct answers without ever truly engaging with the problem). Too much scaffolding, and all you’re really testing is your students ability to copy and paste from a set of project instructions (granted, that can be a useful skill in its own right).

To properly scaffold project instructions, the first few steps should start by telling students exactly what to do. “Open this file. Find this code section. Go make this exact code change in line 5.” As students work, each step should offer a bit less direction. Next, students will be applying the same idea in different place. As the steps progress, they’ll be told less and less what to do, applying the main idea in new ways. Eventually, the instructions will have them adding new features without explicit direction.

As an example, several years ago I authored a project called “Rock Dodger” that was embedded in a year-long Java curriculum for high schoolers. The cored idea was teaching students when and how to use getter and setter methods to enable interaction between objects.

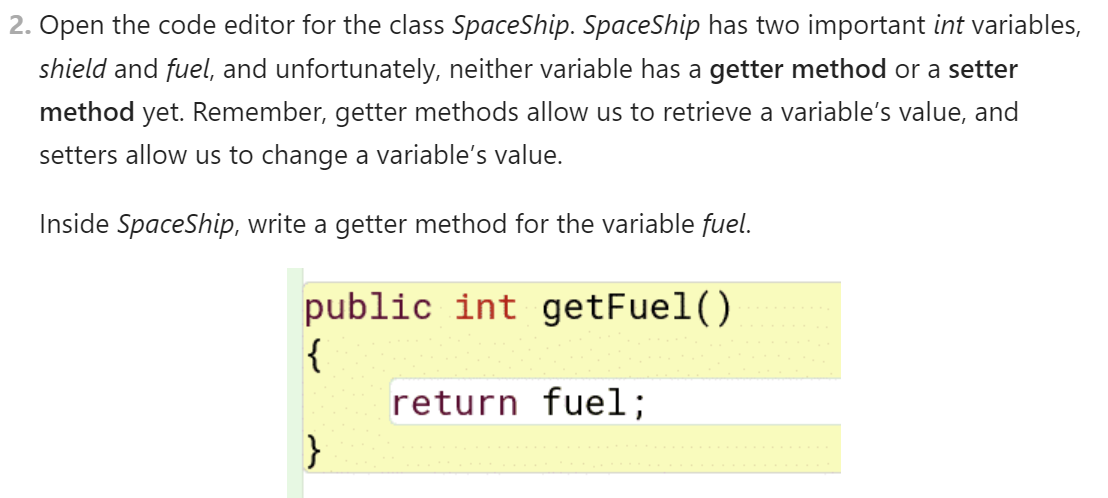

One of the first steps showed students exactly what to do, like this:

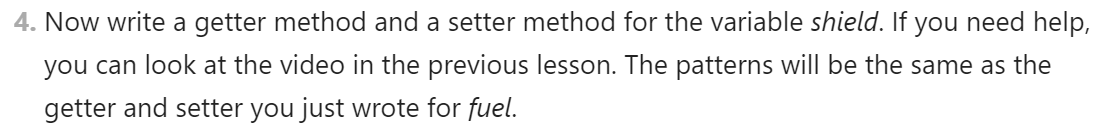

A couple steps later, the training wheels started to come off just a little bit:

As they work, the project instructions direct students to look at former steps to figure out how to perform new, similar tasks:

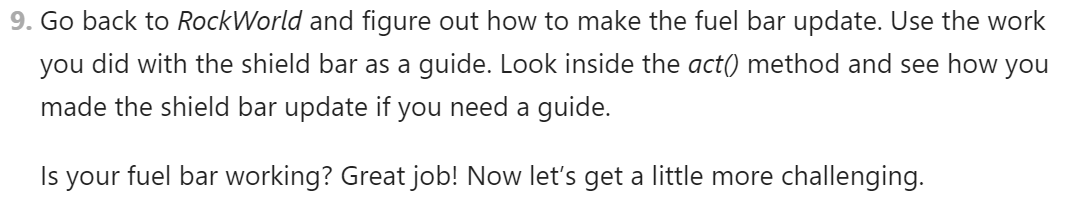

Until finally, we expect the students to think critically about how to proceed forward on their own:

Until finally, we expect the students to think critically about how to proceed forward on their own:

Because of how the project is scaffolded, students are slowly taught how to reason through each step and guided towards creative, independent thinking. Building a computer science curriculum this way doesn’t just build knowledge, it builds skills. A well-scaffolded curriculum also supports students and teacher of all levels and backgrounds, not just those with the highest aptitude or outside experience.

Because of how the project is scaffolded, students are slowly taught how to reason through each step and guided towards creative, independent thinking. Building a computer science curriculum this way doesn’t just build knowledge, it builds skills. A well-scaffolded curriculum also supports students and teacher of all levels and backgrounds, not just those with the highest aptitude or outside experience.

That ends my ruminations on the importance of scaffolding in computer science curriculum. In a week or two, I’ll post some writings on the importance of project-driven curriculum.

Last modified on 2025-12-17